by Fran Amery, Stephen Bates & Steve McKay

Ever wondered about the gendered dimensions of the REF returns and rankings for the Politics & International Studies Unit of Assessment? Well wonder no longer.

1320 people were submitted to the Politics & International Studies Unit of Assessment of REF 2014. Of these, 929 were men, 387 were women with 4 not known*. This means that, excluding not knowns, 29.4% of those submitted to the REF were female, a slightly lower percentage than the percentage of UK-based female political scientists in Bates et al.‘s 2011 survey of the profession (see Table 1).

Table 1: Number & percentage of male & female political scientists submitted to REF 2014 & in 2011 Survey

Tables 2 and 3 show breakdowns of these statistics in terms of job title and gender**.

Table 2: Numbers of Male & Female Political Scientists by Job Title and in Total, 2011 Survey & 2014 REF (% in Brackets)

Table 3: Job title by number of male or female political scientists and in total, 2011 Survey & 2014 REF (% in bracket)

These figures suggest that the reason why the percentage of female political scientists submitted to the REF was lower than the 2011 survey is because women are more likely to occupy positions that meant they were unable to be submitted (e.g. they were teaching fellows, etc.), rather than because they were less likely to be chosen. The figures also appear to show that there has been an increase in the number of female professors since 2011 but that there hasn’t been a corresponding increase in the number of male professors. 65 female and 369 male professors were recorded in the 2011 Survey; 87 female and 361 male were submitted to the 2014 REF. This means that 19% of professors submitted to the REF were female (compared to 15% of professors recorded in the 2011 Survey).

It is also perhaps interesting to note the figures for institutions which have moved towards using the more US-leaning titles of Assistant and Associate Professors, rather than Lecturers and Senior Lecturers (the figures are included in the equivalent job category in the Tables above). While numbers are small, some 87% of assistant professors were male (much higher than for lecturers), as were 65% of associate professors (about the same ratio as for senior lecturers).

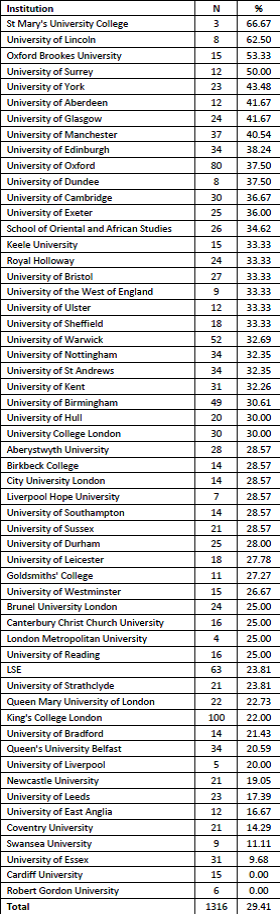

In terms of individual institutions, the institutions which submitted the highest percentage of female political scientists to the REF (although sometimes with a small total number of people submitted) were: St Mary’s University College; Lincoln; Oxford Brookes; and Surrey. The institutions which submitted the lowest percentage of female political scientists were: Cardiff; Robert Gordon (both of which submitted no female political scientists); Essex; and Swansea (see Table 4).

Table 4: Number & percentage of female returnees to the REF by institution

Of those institutions for which we had both sets of data (n=53), 9% submitted the same percentage of female political scientists as the percentage recorded in the 2011 survey (highlighted in green), 45% submitted a greater percentage (yellow), and 45% submitted a lower percentage (blue; see Table 5).

Table 5: Comparison of 2011 survey & 2014 REF in terms of % female political scientists

Table 6 shows a ranking of institutions in terms of the Seniority Sex Gap (SSG)^ for those scholars returned to the REF. A positive rating means the average female political scientist is more senior than the average male political scientist; a negative rating means the opposite. It shows that, taking all institutions into account, the average female political scientist returned to the REF holds a position just under a third lower than their male counterpart does. On this rating mechanism, the average male political scientist has a seniority rating of 3.07 (just over a senior lecturer/reader), while the average female political scientist has a seniority rating of 2.73 (just over a quarter under a senior lecturer/reader).

Table 6: Seniority Sex Gap by Institution

This is the first of two blog posts on gender & the REF. The next one will look at the various rankings of the REF. You may also be interested in this post on what titles of pieces submitted to the REF tell us about (sub-)disciplinary trends.

* Data on the gender and job title of the person submitted to the REF was collected using websearches of university and other relevant websites. This data was collected between the 1st and 6th February 2015 which means that the job title recorded may be different to when the person was submitted to the REF. Thanks to Darcy Luke for collecting this data.

** All the following figures excludes the not knowns.

^ The average seniority for male and female political scientists is produced by, first, giving a weighting to each category of job title (1 = Teaching/Research Fellow, or equivalent; 2 = Lecturer/Senior Research Fellow, or equivalent; 3 = Senior Lecturer/Reader, or equivalent; and 4 = Professor, or equivalent). The sums of each weighting multiplied by the number of male or female political scientists in the corresponding category of job title is then divided by the total number of male or female political scientists to produce a rating for both female and male political scientists. It is not possible to offer comparisons with the findings of the 2011 survey because a slightly different methodology was used to produce the figures for the REF.

Reblogged this on UK PSA Women & Politics Specialist Group.

Pingback: Gender & the Research Excellence Framework: An Analysis of the Politics & International Studies Unit of Assessment (II) | Stephen R. Bates